For nearly 20 years, Andrew Knight has been interested in unobtrusive research methods. A professor of organizational behavior, he’s passionate about learning how people can best work with one another, and his current focus is on improving people’s virtual collaborations.

Knight used the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 as a spark for packaging something he’d been experimenting with to analyze photos and video recordings.

The result: a new, free software named zoomGroupStats.

“With teaching shifting to a virtual realm and a pressing need to understand virtual collaboration, I was motivated to accelerate the development of this software,” he said.

The package is to enable researchers to use the virtual meetings platform Zoom to collect data that illuminates how people interact with one another, Knight said. With it, users can quickly turn files downloaded from Zoom into datasets, analyze the dynamics of spoken and text conversations in virtual meetings, and extract information from the video feeds of virtual meetings.

Who do you imagine using this software? And for what?

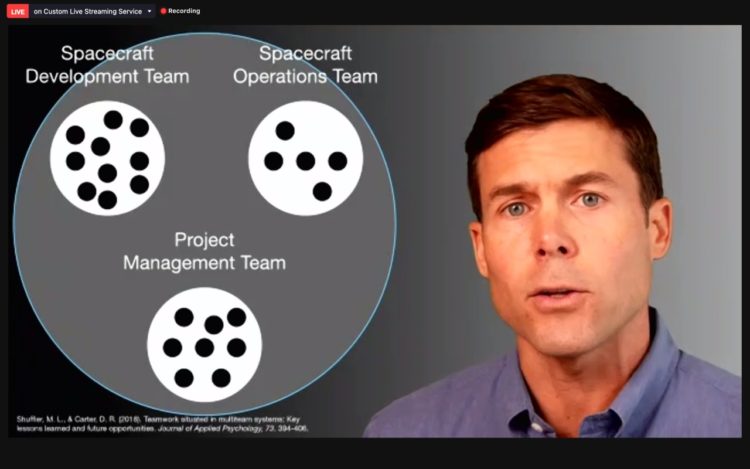

The first category is researchers. The software is currently designed especially for researchers who study teamwork, negotiations, interpersonal relationships and group dynamics. However, the basic functionality of the library would be useful to anyone who wants to extract insights into conversation dynamics and emotion during virtual meetings.

The second category is teachers running virtual classes. The software can provide insights into who is engaged in the conversation during a class (i.e., class participation) and the ways in which people are making contributions (e.g., vocal contributions, text-based chat contributions).

The third category is leaders and managers who conduct virtual meetings. When paired with a web application that I created (http://meetingmeasures.com), the software can give leaders feedback on how effectively they facilitate virtual meetings.

How easy are the tools to use?

When paired with the step-by-step tutorial that I created (http://zoomgroupstats.org/), I hope the library is accessible for anyone with a basic level of proficiency with the open source statistics software R. Some elements of the functionality—such as the capacity to read the emotional expressions of people’s faces through their cameras—requires an additional level of proficiency in setting up and configuring Amazon Web Services.

What are the privacy concerns with this software?

Like any use of recorded human behavior, users must take into account privacy considerations. In a way, the privacy concerns for research are equivalent to more traditional methods (e.g., having human research assistants rate and classify people’s behavior from a video recording). However, people have variant perspectives on software-based “automatic” coding compared to human-based coding of their behavior. As a general rule, anytime a meeting is being recorded, a meeting leader should explicitly request permission to record from all meeting participants.

How have you used your software?

I’ve used this for research and teaching purposes so far. On the research side, I have primarily been working to validate a set of metrics that can be automatically derived from a virtual meeting vis-à-vis traditional, survey-based metrics. This is important to situate the automatic metrics within the current landscape of research on interpersonal relations and group dynamics.

On the teaching side, I have used this software in combination with my Meeting Measures web application to give students feedback on their virtual meetings. This is helpful for showing students when, for example, they dominate the conversation or make inadequate contributions to their team meetings.

So the software is free?

Yes. The R package is free and open source. It is available through the web-based repository (Comprehensive R Archive Network, or CRAN) that is used to distribute packages for R.

Top photo: Professor Andrew Knight teaches a hybrid course in September 2020 in Emerson Auditorium. In front of him, socially distanced students site in the auditorium, while behind, students participating remotely appear on screen.