Former Dean Stuart Greenbaum offers his tribute to Ron Allen

during a retirement reception at Kopolow Library

in Simon Hall on October 12.

When Ron Allen first arrived on WashU’s campus for a new job as business school librarian, there wasn’t one—at least, not one adequate to serve a world-class business school.

In 1986, Robert Virgil was dean, on a mission to raise Olin Business School’s profile among global business schools. Simon Hall was under construction and a new, state-of-the-art business library was part of the plan to help propel Olin to new heights. Allen was to be the first to build the library from a tiny nook and to hold an endowed directorship for the position as the Asa F. Seay Librarian.

“There was a sense of starting from nothing and growing this library into a first-rate service for faculty and students,” Allen recalled on October 5, on the occasion of his retirement from WashU, 33 years after his arrival. The New York City native—who confessed that “I don’t know if I could have identified St. Louis on a map”—spent three decades building, defending, and morphing the library through changes in leadership and technology.

“He was a change agent like nobody else over the course of his career,” said Ron King, Myron Northrop Professor of Accounting, in his tribute remarks. “The heart of the school was the library.”

At an event in the ornate reading room at the Al and Ruth Kopolow Business Library, three former deans and Todd Milbourn, vice dean and Hubert C. and Dorothy R. Moog Professor of Finance, shared their recollections of Allen’s career and contributions.

Milbourn recalled how Allen “got me wired in” as a brand new faculty member in the business school when he arrived, describing Allen as a partner in research who would find and help faculty exploit new data sets for their work.

Former deans Stuart Greenbaum and Mahendra Gupta recalled occasions when they tried to commandeer space from the library to accommodate expanding programs at Olin—attempts Allen rebuffed every time.

“You fell in love with the place when you walked into Kopolow,” Greenbaum said, crediting Allen with the environment he’d created. Gupta built on that remark, calling the library “the intellectual future of the school.”

When Allen came to WashU to run the business library, it was a standalone entity. It’s since been absorbed as part of the WashU library system. He said he’s come to terms with the idea of retirement and is looking forward to downsizing from a house to a Central West End apartment and his Florida condo.

“His handprint is all over this library and the way it was shaped and developed,” said former Dean Robert Virgil. “It was why our students wanted to stay here and study here.”

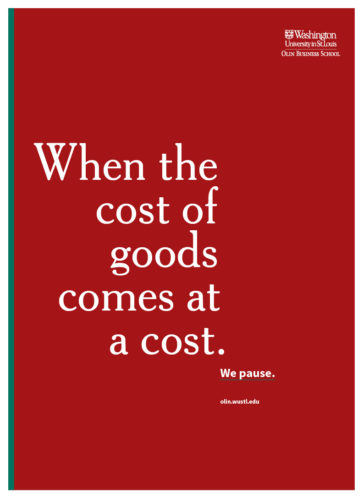

In one of Olin Business School’s newest magazine ads, white text pops from a field of rich red in type that evokes a sense of strength and wonder. Just a few words, strategically aligned on the page, draw the reader into a story of unknown origin—and clear gravity.

In one of Olin Business School’s newest magazine ads, white text pops from a field of rich red in type that evokes a sense of strength and wonder. Just a few words, strategically aligned on the page, draw the reader into a story of unknown origin—and clear gravity.

The crowd applauded after watching the brand identity video (see above).

The crowd applauded after watching the brand identity video (see above). The messaging comes together in a simple positioning statement that boldly declares who we are and how we’re different from other top business schools: “As a premier educator of business professionals, Olin Business School champions better decision-making by preparing and coaching a new academy of leaders who will change the world, for good.”

The messaging comes together in a simple positioning statement that boldly declares who we are and how we’re different from other top business schools: “As a premier educator of business professionals, Olin Business School champions better decision-making by preparing and coaching a new academy of leaders who will change the world, for good.”