On August 25, Hurricane Harvey hit the Texas Gulf Coast with severe effects in the Houston metropolitan area, other parts of Texas, and Louisiana. When such disasters happen, we are all emotionally affected by the human tragedy, injuries and death (close to 50 deaths accounted for so far), devastation of properties that families had worked long and hard to build, and the desperation that follows as people try to pick up their lives.

Part of a supply chain manager’s job is to think about how such natural disasters will affect their company’s supply chain. In the tightly connected global supply chains of today, there is a high likelihood that there will be an impact, regardless of how far away the event occurred. Many recent disasters serve as examples of this global impact: Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, the Japanese earthquake and tsunami north of Tokyo, or the flooding in Thailand. American and Western European car companies’ plant operations that sourced components from Japanese suppliers were halted within a week. And PC makers were disrupted due to the loss of 40% of worldwide capacity in hard disk drives in the Thai floods. Hurricane Harvey is another strong reminder of lessons learned in supply chain risks and their management, and how devastating and far reaching the effects of such events can be for supply chains.

It is perhaps a bit hyperbolic, but rightly so, to say that the whole world will feel the pinch of Harvey.

As a supply chain manager, your first level reaction is to consider which customers, products, facilities, employees and suppliers will be the most exposed to Hurricane Harvey. What is the overall revenue exposure, and how long will it take to recover? Houston is a metropolitan area with an economic output of half a trillion dollars, and companies in almost all industries have some type of location or sales outfit there. In most cases, the impact will be nothing more than a flooded basement, power outages, and restricted access to facilities due to other infrastructure failures, and some delayed shipments. Home Depot and Lowes reported close to 60 temporary store closures due to flooding, but given the increased demand of their products in infrastructure and home improvement projects, their recovery will most likely be swift.

The most important part, and the company’s first priority, is to check for employees that are located in affected areas, and quickly verify their wellbeing. Procter & Gamble’s Folgers plant in New Orleans was exposed to Hurricane Katrina, and one of the company’s biggest challenges after the event was tracing the fates of its employees and ensuring their safety. In the oil drilling, refining, and chemical manufacturing industries, some of the main production and distribution facilities are in the Houston area, so one needs to think about the first order effects on businesses from flooded, non-operable facilities. Some news outlets reported that 25% of the U.S. oil refining capacity was closed by the end of August, including the two largest refineries. This will imply serious disruptions to gasoline supply in the Southeast and the Midwest. Based on my own causal observations, gas prices in the St. Louis area were 20-30 cents higher this Labor Day weekend, with increases expected to last for a month. Depending on how fast the refineries recover, and the overall supply conditions of crude oil in the area, fears of fuel shortages might drive gas prices up, inevitably affecting the logistics costs of all businesses. Twenty percent of the offshore crude oil supply was shut down as flooding disrupted wells and caused pipeline operators to close their taps. But this might be welcome, as some of the crude oil demand is down at the same time due to the idled refineries. Crude oil prices slid down by almost 50 cents a few days after the hurricane. Natural gas production has been disrupted as well, with potential implications for heating and power generation fuel supply and prices.

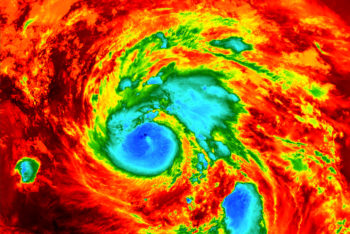

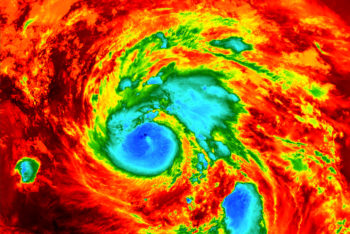

Hurricane Harvey

Infrastructure damages to ports, airports, and roads have immediate effects on all supply chains. The major airports in Houston were not affected much beyond some delayed flights (around 1,000 flights over a day or two) and unexpected delays in reopening. Even smaller airports were back in operation by the end of August. However, port traffic is more seriously affected. The ports of Houston and Corpus Christi are two of the largest in the U.S. (second and sixth, respectively), with both ports’ operations severely affected for more than a week. East of Houston, Port Arthur is completely underwater, and the closure of regional railways and highways led to FedEx, UPS, and USPS halting all deliveries to impacted areas. Major railroads (KC Southern, BNSF, Union Pacific, et al.) completely halted or reduced their level of operations around the coastal region and surrounding areas. Facilities receiving shipments from suppliers in the area should expect moderate to significant delays. Retailers and manufacturers far from Texas will be affected by the impact on transportation and rail networks, and should expect increased logistics costs to eat into their margins. In the trucking industry, which had capacity shortages prior to the event, the impact will be an additional shortage of 10%. As increased emergency shipment prices and demand shift some of the capacity to the Southeast, prices will rise nationwide. Capacity shortages and increased fuel costs might have a double-whammy effect on transportation logistics costs for all companies, particularly those in the grocery, food, and beverages industries.

As any supply chain manager understands all too well, it is not necessarily the original event (in this case, the hurricane), but the ripple effects of the event that cause the major supply chain disruptions.

In retrospect, the Japanese earthquake of March 2011 was the least of their worries. About half an hour after the shaking ended, a tsunami—two to three times higher than projected—inundated the shores nearest the quake’s epicenter. And 180 kilometers away from the quake’s epicenter, the nuclear power plant at Fukushima Daiichi flooded, incapacitating the backup diesel generators responsible for cooling three of the six nuclear reactors. Within 24 hours of the tsunami, these reactors exploded, spreading harmful radiation. Hurricane Harvey caused a similar scenario, albeit with substantially fewer consequences. As the hurricane blew in, employees of the Arkema chemical plant in Crosby, TX had to make sure that the plant’s volatile chemicals remained refrigerated. When the power went out and the floodwaters knocked out the plant’s generators, the only alternative was to move the chemicals to nine huge, refrigerated trucks, each with their own generator. However, when six feet of water swamped the trucks (described by an Arkema spokesman as “watching physics at work”), a series of explosions followed. Fortunately, the fire and blasts were not as dire as feared, but in the eyes of a safety investigator, it was “a wake-up call for an industry and their safety regulators who have not adequately taken action on lessons from Hurricane Katrina, as well as the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan.” A large number of the more than 1,300 chemical plants in Texas—many of them driven there by the access to gulf ports and shale gas operations—are vulnerable to flooding events.

If someone were trying to anticipate the ripple effects on supply chains resultant from the Harvey disaster, ethylene and its derivative products, polyethylene and PVC, will be the proverbial “usual suspects” to cause a bullwhip effect. Sixty percent of the U.S. ethylene capacity has been closed due to Harvey-related floods. Ethylene and its derivatives are used to produce plastics, antifreeze, house paint, vinyl products, and rubber; thus, shortages of it will affect multiple manufacturers and consumer markets. With the U.S. accounting for 20% of the global ethylene production, and with current utilization being very high, any small hiccup will drive supply-demand imbalances. It is too early to predict the magnitude of shortages, but petrochemical plants in the Gulf region are already advising customers of their inability to meet their commitments for polyethylene, polypropylene, and PVC. And the “bullwhip” game begins (!) with bigger firms hoarding capacity, smaller ones scrabbling to find any capacity at any price, suppliers rationing orders, inflated projections of demand, and rapidly escalating prices. The complexity of the ethylene manufacturing process, the longer restart times for closed operations, the lead times required to ensure safety of operation, and the current transportation bottlenecks make for an inflexible supply chain, incapable of adjusting to any small supply or demand shocks. Ethylene-dependent industries are in for a roller coaster ride in the next few months, and the rest of us might have to pay for it.

There are two main tools the supply chain manager possesses to effectively mitigate the damage of major disaster events and drive the quick recovery of supply chains. The first is redundancy, as in having extra resources, capacity, and people, and the second is operational flexibility, as in dynamically reallocating the resources based on updated information and the needs of the realized situation. Thus far, both of these tools have been deployed by federal agencies and companies in handling the Harvey disaster aftermath. Experts expect that the effects on gas prices will be less severe because gasoline inventories are higher than they were in the aftermath of Hurricane Ike in 2008. Also, the crude oil supply concerns can be alleviated through some release of oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserves by the U.S. government. Going forward, it is better to plan ahead for some excess capacity and location diversification in our stretched energy infrastructure, as the heavy concentration along the Gulf Coast, together with very high utilization, makes it particularly vulnerable to natural disasters. Our ports have learned from the past, either through hurricanes or labor strikes, to be ready to effectively reroute shipments to meet logistics needs for customers. Global logistics companies have real-time information on the location and the container load of their ships and can drive dynamic rerouting as needed. Maersk is dynamically deciding whether to wait at the Houston port or reroute its container ships to other ports. Manufacturers fearing shortages of ethylene supplies are looking for substitute materials or alternative global suppliers. Hopefully, some of the downstream retailers have adequate inventories of needed products to handle a short period disruption in logistics services. Alternatively, price increases can also drive the demand away from low inventory products to other substitutes.

Wall Street is counting on the resilience of the supply chains. The stock markets have weathered the Harvey storms and have even gained in the aftermath. Effectively, the market is counting on companies to have learned lessons from the past and to have prepared their supply chains accordingly, either through careful planning, redundancy, or operational flexibility to manage the impacts of this disaster. The markets are comforted by the fact that any financial losses in the region will not propagate, as home insurance policies are not covering flooding and the major insurers will not be exposed to catastrophic losses. Other companies’ exposures on the service and delivery side are dealt with by supply contracts, which include “force majeure” clauses for events that result from natural and unavoidable catastrophes beyond the firms’ control. But I prefer the more optimistic explanation that markets trust the supply chain executives as consummate risk managers who have learned the lessons of the past. Hopefully they will be able to use the real-time information and data they have, and exercise a flexibility in their decision making to adjust operations for whatever outcomes result. Markets are betting that the companies using the best risk management techniques will find competitive opportunities against less-prepared rivals, and fully leverage the new opportunities created by the recovery efforts. Let us all be optimistic for the resilience of our supply chains and the fast recovery of the Gulf Region!

Panos Kouvelis is the Director of The Boeing Center for Supply Chain Innovation and Emerson Distinguished Professor in Operations and Manufacturing Management. He has consulted with and/or taught executive programs for Emerson, IBM, Dell Computers, Boeing, Hanes, Duke Hospital, Solutia, Express Scripts, Spartech, MEMC, Ingram Micro, Smurfit Stone, Reckitt & Colman, and Bunge on supply chain, operations strategy, inventory management, lean manufacturing, operations scheduling and manufacturing system design issues.

Panos Kouvelis is the Director of The Boeing Center for Supply Chain Innovation and Emerson Distinguished Professor in Operations and Manufacturing Management. He has consulted with and/or taught executive programs for Emerson, IBM, Dell Computers, Boeing, Hanes, Duke Hospital, Solutia, Express Scripts, Spartech, MEMC, Ingram Micro, Smurfit Stone, Reckitt & Colman, and Bunge on supply chain, operations strategy, inventory management, lean manufacturing, operations scheduling and manufacturing system design issues.

For more supply chain digital content and cutting-edge research, check us out on the socials [@theboeingcenter] and our website [olin.wustl.edu/bcsci]

• • •

A Boeing Center digital production

Supply Chain // Operational Excellence // Risk Management

Website • LinkedIn • Subscribe • Facebook • Instagram • Twitter • YouTube

Panos Kouvelis is the Director of The Boeing Center for Supply Chain Innovation and Emerson Distinguished Professor in Operations and Manufacturing Management. He has consulted with and/or taught executive programs for Emerson, IBM, Dell Computers, Boeing, Hanes, Duke Hospital, Solutia, Express Scripts, Spartech, MEMC, Ingram Micro, Smurfit Stone, Reckitt & Colman, and Bunge on supply chain, operations strategy, inventory management, lean manufacturing, operations scheduling and manufacturing system design issues.

Panos Kouvelis is the Director of The Boeing Center for Supply Chain Innovation and Emerson Distinguished Professor in Operations and Manufacturing Management. He has consulted with and/or taught executive programs for Emerson, IBM, Dell Computers, Boeing, Hanes, Duke Hospital, Solutia, Express Scripts, Spartech, MEMC, Ingram Micro, Smurfit Stone, Reckitt & Colman, and Bunge on supply chain, operations strategy, inventory management, lean manufacturing, operations scheduling and manufacturing system design issues.