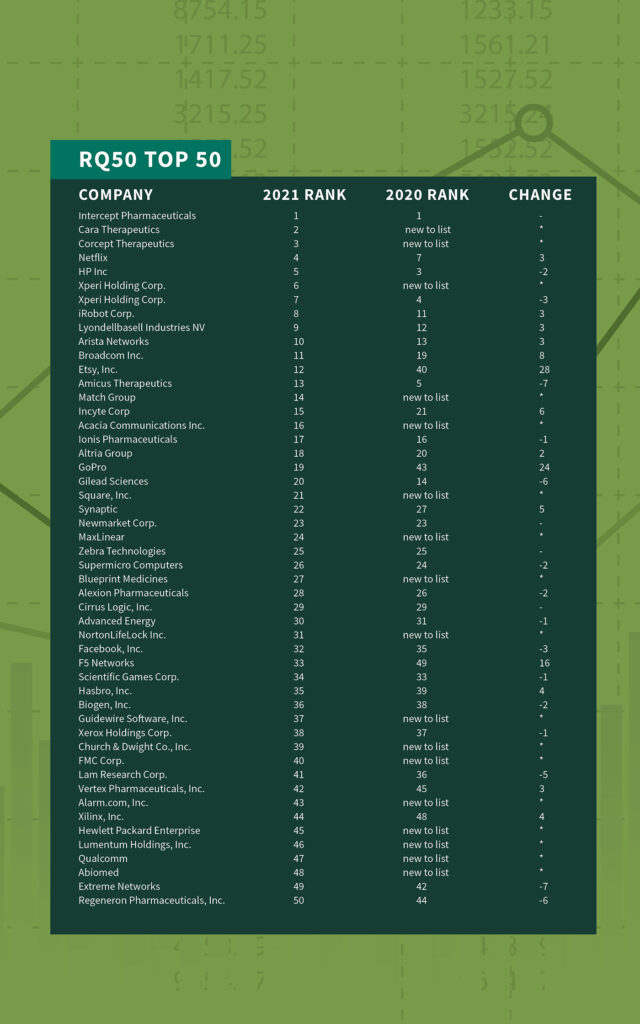

Pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies topped the 2021 RQ Top 50 list of the most innovative U.S. companies. The annual ranking identifies the smartest R&D spenders – those companies that both spend big (at least $100 million in R&D) and provide the greatest returns to shareholders from that investment.

Notably absent from the list were the three most attention-grabbing pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies of the year – Pfizer, Moderna and Johnson & Johnson.

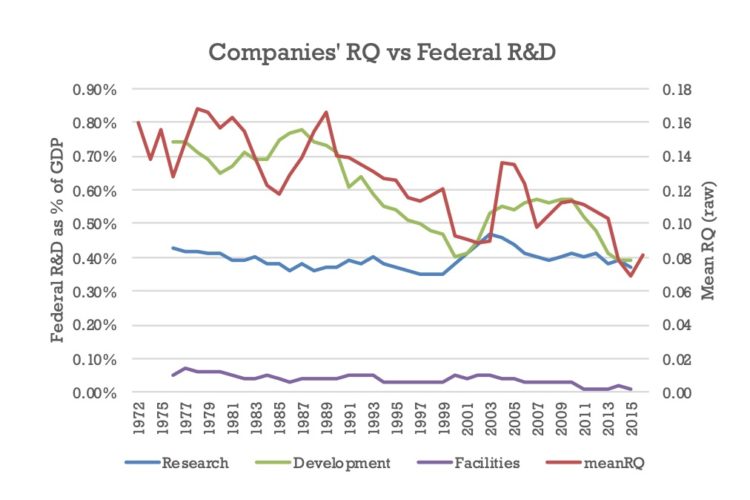

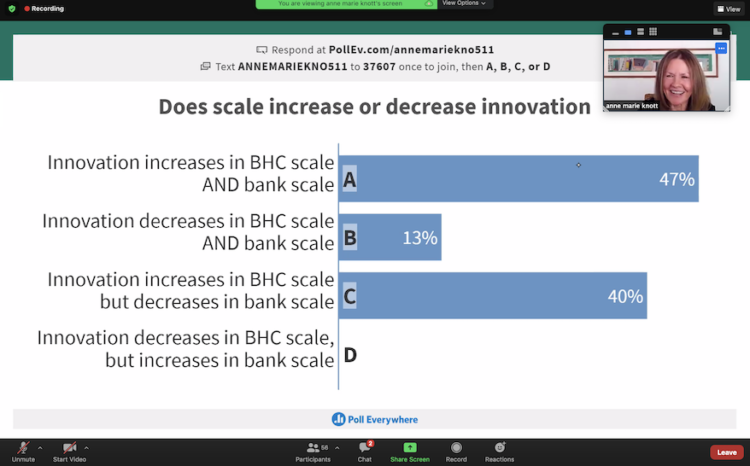

That’s because the RQ50 is not like other innovation rankings. Developed by Anne Marie Knott, the Robert and Barbara Frick Professor in Business at Washington University’s Olin Business School, RQ (research quotient) measures R&D productivity in theoretical models linking R&D investment to revenue growth and market value – precisely the outcomes executives and investors care about, Knott said.

“RQ essentially measures how smart companies are. Just as high IQ individuals solve more problems per minute, high RQ companies solve more technical problems per dollar,” Knott said.

“While most of the market still thinks R&D spending is the best gauge of companies’ innovativeness, it’s not. It’s quality not quantity of R&D spending that matters.”

The proof is in the numbers: The RQ50 portfolio historically outperforms the S&P 500, despite the fact that the two portfolios bear the same level of risk (beta), Knott said.

What does it take to make the RQ50?

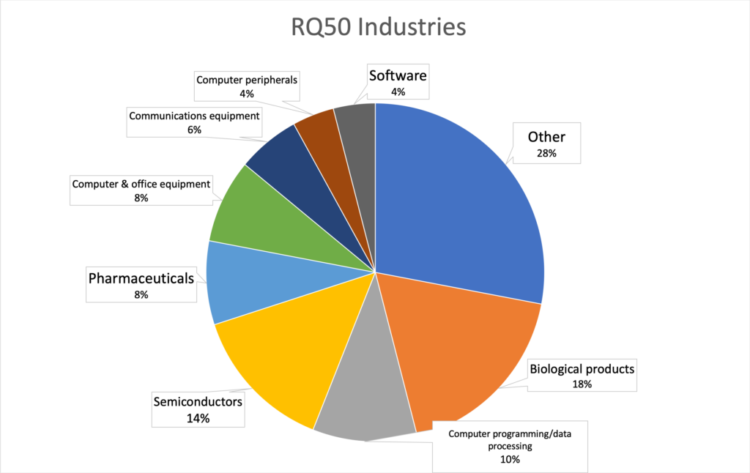

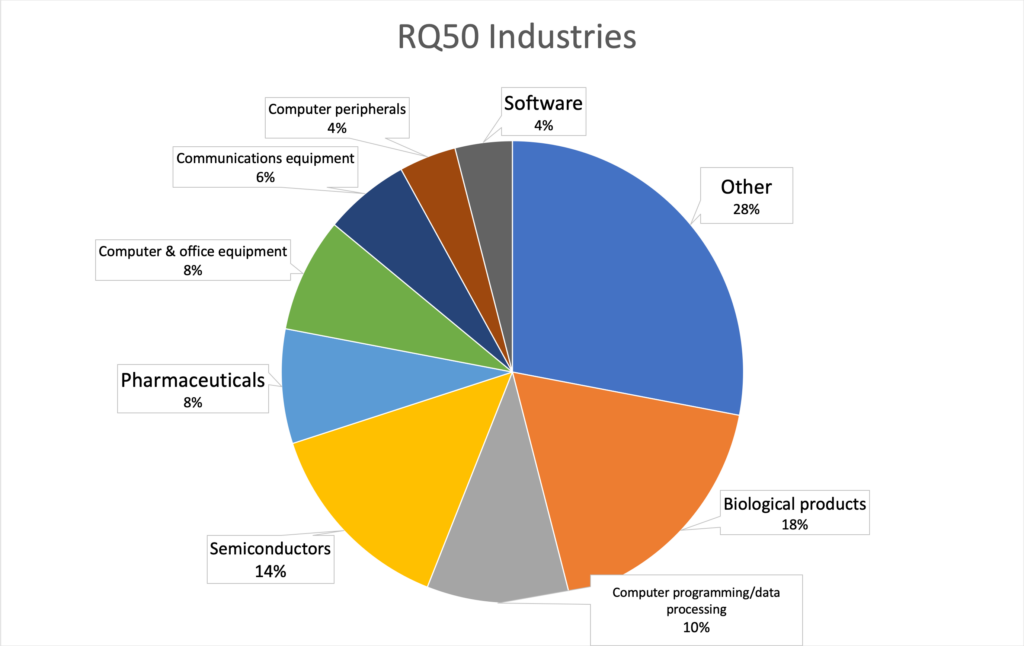

The 2021 RQ50 represents a broad swath of the economy. The biggest representation comes from pharmaceutical and biotechnological companies, which comprise nine of the top 50, or 18%. Makers of semiconductors make up 14% of the list followed by computer programming at 10%. By contrast, 28% of the RQ50 are the only firms in their industry to make the cut.

“So it’s not the case these firms are all riding the same wave of opportunity,” Knott said. “The RQ50 firms are standouts in their respective industries.”

Now in its eighth year, the RQ50 ranking is fairly stable: 66% of firms from the 2020 ranking appear again in 2021. According to Knott, that’s because firm capability changes slowly.

Of the 50 companies who made this year’s ranking, six have made the RQ Top 50 all eight years since CNBC published the initial RQ50 in 2014. These standouts include Hasbro, Lam Research, Netflix, NewMarket, Synaptics and Xilinx.

New to the list

Seventeen companies are new to the RQ50 list. How did they make it?

- Alarm.com, FMC, Guidewire Software, Match Group, NortonLifeLock and Qualcomm were close last year, but ascended this year.

- Abiomed, Church & Dwight Co. and MaxLinear crossed the $100 million R&D threshold in FY2020.

- Cara Therapeutics – No. 2 on the list – was excluded last year because its R&D exceeded revenues.

- Prior to FY2020, Acacia Communications, Blueprint Medicines, Corcept Therapeutics, Hewlett Packard Enterprise, Lumentum Holdings, Square and Xperi Holdings hadn’t been publicly traded and conducting R&D for enough years to form their RQ.

Who dropped out?

In order for 17 firms to ascend, another 17 had to drop out. What happened to them?

- AMAG Pharmaceuticals and The Meet Group were acquired.

- Retrophin rebranded itself and now trades under a different name.

- Halozyme Therapeutics and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals dropped out because their R&D spending fell below the $100M threshold for inclusion.

- Arena Pharmaceuticals, Enanta Pharmaceuticals, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals and PTC Therapeutics no longer have revenues that exceed their R&D, a criterion for inclusion.

- Allison Transmission, Dow, Intuitive Surgical, FireEye, Sirius XM, Take-Two Interactive, United Therapeutics and Veeva Systems failed to maintain RQs sufficient to keep them in the top 50.

COVID-19’s effect on innovation

While the COVID-19 pandemic shut down manufacturing lines and disrupted global supply chains, research and development – at least so far – appears to have continued its upward trend. During FY2020, which for some ended in June 2020 and for others not until May 2021, R&D spending in absolute dollars increased by 6%. During this same time period, revenues fell on average 10%, making the R&D investment even more significant.

“In most cases, firms committed to their FY2020 R&D spending before the pandemic. So it’s still too early to measure the pandemic’s full impact on firm R&D investment,” Knott said.

“However, I’m cautiously optimistic that firms will continue to prioritize R&D because if there’s anything the pandemic has taught us, it’s the importance of innovation.”